Operation Flashpoint demo

I just thought this video was an interesting demo of the state of 3D-graphics.

Gabe Newell (Valve) and the Game Industry

A few news articles have been coming out of the DICE Summit. In an article titled, “The Very Different Gaming World Gabe Newell Wants”, Newell had some thoughts on “how he thinks the video game industry should work”.

-Pricing that’s always in flux: Are you ready for the price of a game to go up and down regularly? “One of the things that annoys me is the inefficiency in pricing we have in our industry,†Newell said. He doesn’t like how rigidly prices are set in stores and how slowly those prices are changed… Valve has hired an experimental psychologist to concoct new sales promotions, one possible idea being to reward every 25th purchaser of “Left 4 Dead†with a free game on Steam. Newell joked that this person is “turning us to the dark side of B.F. Skinner.â€

Hm. I’m not sure that I’d categorize this under “how the gaming industry should work”. I think what Valve is doing with the price fluxuations is this: attract attention. By having sales, they have an excuse to get into the gaming news. They also give people a reason to keep checking their website (any sales yet)? If you can keep people coming back to your website, odds are better that they’ll buy something – maybe even buying/trying a different product from Steam. As far as I can tell, it’s worked pretty well. I saw gaming websites talking about Valve’s “Left 4 Dead” sale. For example, Joystiq posted this article: “This weekend: Left 4 Dead 50% off on Steam”. Price fluxuations = excuse for gaming websites to talk about you = free advertising.

-Frequent content updates: Newell said “Team Fortress 2″ has received 63 updates from Valve in the last 14 months. That is the future, he told the developers in the audience: “You’re going to be touching [your customers] not every three years but every three weeks — and hopefully even more often than that.

Wait – this if how the gaming industry is supposed to work? If you do the math, there, you’ll see that 63 updates in 14 months is more than one update per week. One of my irritations with Team Fortress 2 was that they were always updating it. Want to play a quick game before you go to bed? Oops! You have to download a patch before you play. Hope you don’t mind a 20 minute download first. One of the other problems that happens with PC games is that the ability to patch games after release means developers feel less bad about releasing a “not quite complete” games, knowing that they can patch it after the fact. One guess here is that Gabe wants to make sure people are tied into the Valve service (since patches are only available through your account) – which means you bought your game (and didn’t pirate it). Frequent updates means pirates are running old versions, and if you want the latest fixes, you’d better buy it. It certainly keeps the uploading-pirates and downloading-pirates busy. I’m doubtful that it improves anything for gamers, but if it helps Valve shake-off some pirates and get some more sales, then gamers are helped indirectly.

-Video game companies acting as “entertainment companiesâ€: Newell said he is “obsessing†over gamers’ expectations for “what kind of entertainment company they want us to be.†They are fans of properties, not forms of entertainment, fans, to use his example, of Harry Potter, as opposed to just Potter books or just Potter movies. As a result, he said he is moving away from thinking of Valve as a video game company. One example is the introduction of “Team Fortress 2″ video shorts made by Valve. The next will be that same team’s “TF2″ comics.

Selling merch – aka: opening up another revenue stream for the company. Not a new idea, but not a bad idea, either.

-No DRM should be offered that can be thought of as DRM: Newell believes that digital rights management software that is presented as copy-protection gives a game a stink. It leaves customers unsure about how flexibly they can access their games. So they turn to pirates who offer games with fewer strings, he suggested. “There is evidence anecdotally that DRM is increasing piracy rather than decreasing piracy.†Valve’s solution: battle the pirates by providing better services than the pirates do. The effectiveness of pirates, he said, is to get content to people who want it more swiftly and easily than the companies who make the content do. An outfit like Valve, however, can get provide even better service, even by doing something as intrusive as data-mining their customers’ computers — as long as they are transparent about it and can prove to the customer that taking such measures will make the customers’ games better.

Well, this isn’t really news coming from Valve. I’m always amused when people rail against DRM, but then suggest following in Valve’s footsteps (oblivious to the fact that Steam is DRM). What this says to me is that there is a right way and a wrong way to do DRM – which is different than view promoted by groups like DefectiveByDesign: that all DRM is bad – inherently wrong, wrong in principle. Ideally, gamers should be able to use their games (and music and movies) without ever running into restrictions during normal use. At the same time, Steam is there to stop people from uploading/downloading games to filesharing sites. Gabe Newell is frequently misunderstood when talking about DRM. You often have to parse his words very carefully to understand exactly what he means. For example, Joystiq paraphrases him as saying “Gabe Newell wants to shake up the way the industry works by … getting away from DRM as copy-protection”. That sentence sounds like Newell is opposed to DRM. He’s not. The original article quotes him as saying: “Newell believes that digital rights management software that is presented as copy-protection gives a game a stink.” Newell is suggesting digital rights management that isn’t presented as copy-protection – it’s presented as a system to automatically download patches, etc. In an article less then six months old, Doug Lombardi (of Valve) was quoted as saying:

Lombardi, and others I spoke to off the record, say that at least for digitally downloaded PC games, DRM and copy protection is here to stay. For Valve the biggest push is to lock down those “zero day” pirates. Day zero is the time between when a game goes gold and when it is available for purchase… The key to making a good authentication system, Lombardi says, is to not stand in the way of customers enjoying what they bought.

By keeping their DRM strings invisible, many gamers seem unaware of the fact that Steam is DRM. I see examples like this all the time:

Valve seems to have managed to simultaneously use DRM and get lots of people to praise them for not using DRM. And, of course, if people break their DRM – well, Valve can fall-back on the fact that only legitimate buyers get the weekly updates mentioned earlier.

-Concept art for everyone: Newell wants creators and customers to be in more direct communication with each other before and after the release of a game. One such method is to show concept art early, which builds buzz. The concept art, Newell said, “is a more effective tool [for building buzz] than most of the advertising around your product.â€

This idea isn’t even remotely new.

It won’t be better graphics that determines a winner in the next console generation (which, of course, it never has been: see the N64, Xbox and PS3). It’ll be the extent to which a console allows game creators “to have this relationship with your customers.†The “this†is everything bullet-pointed above.

True. You want customers coming back to your website over and over. I’m sure the Valve-customer relationship will establish their website as great place to advertise their next game, increase brand recognition, open up more possibilities for selling old stuff / merch, becoming more than just a faceless corporation, etc, etc. The other day, I was thinking about how the games industry is different than a lot of other industries. I don’t really remember what companies made which games, and which games were made by which companies. It’s just not that important because titles are so variable. I’m never in a position where I say, “Oh, Valve made X. I like that game. Here’s another game by Valve. I’ll probably like this one, too.” But, when I’m talking about a musician or an author, I think it’s a different situation – I might buy an album from a musician if I like their other stuff, even if I haven’t heard a single song from that album. And people have a pretty good idea what a book will be like if it’s written by Stephen King. But, we just don’t follow game companies like that. Maybe games are more variable in their execution. What this ultimately means for game companies is that they have to convince customers of the merits of each and every game (rather than relying on an “established reputation”). The relationship Gabe is talking about plays an important role in selling the merits of the next game.

In the end, I don’t think Gabe Newell has much new to say, and it certainly isn’t a “very different gaming world” (as the title of the article suggests). One thing that did occur to me while reading this, though, is that the gaming industry is picking up the same strategies that politicians have used on the campaign trail: repeat yourself constantly. Repeat, repeat, repeat – drill in your ideas over and over because different people are listening each time. It seems like the game companies maintain a set of talking points – stuff they can repeat to game journalists for a story. (I remember Brad Wardell of Stardock doing the same thing.) I hope I never have to play that role. I get really bored of repeating myself.

Pirate Bay Goes To Court

Well, it’s about time, Sweden. The enemies of software development are finally in court. According to articles I’ve seen, the movie, music and software industries are claiming that they made millions of dollars on ads. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but it doesn’t much matter to me whether they got rich (just like it doesn’t matter to me whether or not someone made money when they slashed the tires of my car – they’re still guilty of causing harm). I suppose that’s the justification for the fines, though – the Pirate Bay faces $13 million in fines and up to 2 years in jail.

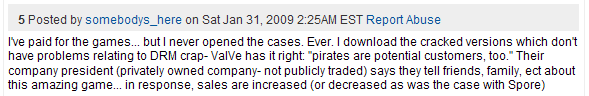

What’s disturbing, however, is the fact that some popular websites have become “no go” areas for anyone arguing that copyright should be respected. Both Digg and Slashdot are strongholds of the pro-piracy / we-ignore-copyright crowd. Here’s two popular comments and one unpopular comment that recently appeared on Digg. Note the vote-up/vote-down counts. Over three hundred people voted these comments up, while 10 voted them down — that’s a 97% vote-up.

For artists, creators, and software developers, it’s a frightening sight.

Escape From City 17 – Part One

A remarkably well-produced fan-movie based on Half-Life 2:

Games Industry Recession?

I have to say that I’m a bit confused. I’ve heard that the games industry is relatively recession-proof. I’ve also heard that game sales were actually up in 2008 compared to 2007. Yet, I keep seeing these kinds of stories in the news:

Sega laying off 560 staff, closing 110 amusement facilities

NCsoft downsizes UK operation, laying off 55 staffers

Midway files for Chapter 11

Square Enix lowers revenue forecast for fiscal year

Activision Blizzard loses $72m in Q4 ’08; outlook misses ’09 expectations

I haven’t quite figured out how both could be true at the same time. Is there some other segment of the games industry (like casual games or Nintendo) that are doing really well, but other parts are getting hit hard? Haven’t quite figured it out yet.

NIN and Business Experiments

I’m always kind of curious about the results when companies try different business strategies. Nine Inch Nails released their last two of their albums for free. Well, free if you wanted them for free. Anyone can download The Slip off of their website for free. You can get the first nine songs of Ghosts I-IV for free. If you want the other 27 songs, you can get them a few different ways: free, $5, $10, $75, or $300 – depending on which package you want. (The packages at $10+ contain various physical media, including DVDs, Blue-Ray with surround sound, etc.)

When they first did this, I wasn’t quite sure about his motivation, but I can imagine a whole bunch of possible motivations – to drive up concert sales, as charity to the fans, faith that fans would pay, etc.

I’ve seen a number of people use the NIN experiments as evidence that giving away music “works for musicians”. In many cases, this is part of a “piracy doesn’t hurt anyone” or “this shows that creative commons works” kind of an argument. For example, RollingStone says: “it proves — along with Radiohead’s chart-topping success of the physical release of In Rainbows — that music fans are willing to support artists even if their music is offered up at no cost.” And Ars Technica: “Nine Inch Nails’ Ghosts I-IV topped Amazon’s digital download charts in 2008, despite being offered to fans free of charge. Creative Commons touts the project as a new model for music… The next time someone tries to convince you that releasing music under CC will cannibalize digital sales, remember that Ghosts I-IV broke that rule, and point them here.”

I’m less certain about the success of these experiments. Here’s the results: NIN Ghosts I-IV was the number one downloaded album on Amazon’s 2008 charts, and brought in $1.6 million in revenue within the first week of sales. Sounds good. But, let’s break down those numbers.

They sold Ghosts I-IV in a few different formats. First, you can download the first 9 tracks for free off their website. All 36 songs are available for free on filesharing networks. Even though it was released it under Creative Commons for free, Trent Reznor didn’t make it too obvious and doesn’t provide a link to download all 36 songs. It appears that most people didn’t know that the full album was available for free. And even if they did know it was free, they wouldn’t know how or where to get it anyway. It’s also available in $5, $10, $75, and $300 Ultra-Deluxe packages. We know that there were 2500 copies sold of the $300 packages. (It pays to have rabid fans.) But we have to guess on the rest. We also know that there were “781,917 transactions“. Obviously, “781,917 transactions” includes people who downloaded the 9 free songs (if it only included actual sales, then 781,917 transactions would be a lot more than $1.6 million).

Here’s what I think is a reasonable guess of sales for the first week:

$300 package x 2,500 copies sold = $750,000

$75 package x 5,000 copies sold (just a guess) = $375,000

$10 package x 10,000 copies sold (just a guess) = $100,000

$5 package x 78,884 copies sold (just a guess) = $394,420

Free download x 685,533 people (88% of the transactions)

——————————–

Total Transactions = 781,917 (the number given to us from this article)

Total Revenue = $1,619,420 (the number given to us from this article)

Now, under these numbers, about 12% or 96,000 people bought something. (If no one bought the $75 or $10 packages, then $5 sales would be at 174,000 copies.) About 700,000 people downloaded the free 9-song version, and who knows how many people downloaded all 36 songs via peer-to-peer networks.

I think one lesson that can be learned is that tiered pricing a big benefit to bands with rabid fans. Most bands couldn’t get away with a $300 package, but (based on my guesses) NIN made 70% of their money from the $300 and $75 packages.

But, I was also surprised by the low number of purchases. Fewer than 100,000 people bought something. Okay, so this is only the first week of sales, but in 2005 (less than a month after their fifth album was released) NIN claimed to have over 20 million albums sold worldwide, which means an average of 4 to 5 million copies sold per album. Additionally, with 800,000 downloads, it means that 7 out of 8 people downloaded the free version and didn’t buy anything. Of course, this makes me question Ars Technica’s conclusion that “[Creative Commons won’t] cannibalize digital sales”.

As far as being the number one downloaded album on Amazon in 2008 (which is based on the entire year, not just the first week’s sales), it looks like NIN routed all their $5 sales through Amazon.com as mp3 downloads. Since Amazon doesn’t have strong mp3 sales in general and all of the $5 sales went though Amazon, and the fact that competing music was split between physical media and downloads as well as being available at a variety of stores, then maybe it’s not surprising that they placed so high in Amazon’s best-selling mp3 list. Digital music downloads are still dwarfed by physical-music sales, making up only 10-20% of total music sales. Given these facts, “#1 downloaded album on Amazon in 2008” is a little less impressive than it sounds.

So, was Reznor’s experiment a success? Does this vindicate Creative Commons as a viable and reasonable alternative to selling music? I’m doubtful. It seems like Reznor has mixed feelings. In an interview done last year (before releasing Ghosts I-IV) Reznor talked about his collaboration with Saul Williams. They put an album together and released it as both free download and as a $5 purchase:

Reznor produced and helped bankroll the album, which debuted November 1. All the more reason why he was stunned when fewer than one in five people who downloaded the music were willing to pony up $5, roughly the cost of a McDonald’s Quarter Pounder.

…

Reznor ended the hoopla last week when he reported on his blog that 154,449 people had downloaded NiggyTardust and 28,322 of them paid the $5 as of January 2. In the blog, Reznor suggested that he was “disheartened” by the results.

…

[Y]ou have a lot of reasons why you [don’t want to buy music from the record labels]. So I thought if you take all those away and here’s the record in as great a quality as you could ever want, it’s available now and it’s offered for an insulting low price, which I consider $5 to be, I thought that it would appeal to more people than it did. That’s where my sense of disappointment is in general, that the idea was wrong in my head and for once I’ve given people too much credit.Saul and I went at this thing with the right intentions. We wanted to put out the music that we believe in. We want to do it as unencumbered and as un-revenue-ad-generated and un-corporate-affiliated as possible. We wanted it without a string attached, without the hassle

…

I’m not saying it was a failure or a success. I think it was both. But it wasn’t 90 percent of the people that showed up paid us what we asked for. Nor did I ever think it would be. I’m not sure what I did expect.But I’ve found it entertaining reading different people’s perspective on the Web, what they’ve thought of what I’ve said. There’s been a wave of people that said, ‘Oh, that’s depressing. Only 18 percent chose to pay for it.’ Another whole wave of people feel just the opposite. I don’t really know.

CNet News: Trent Reznor: Why won’t people pay $5?

Now, looking at the downloads versus purchases of Ghosts I-IV, we can say that only about 12-13% of the people paid $5 or more for the 36-track album (as opposed to downloading the free 9-tracks from the NIN site). Additionally, a lot of people got the music via peer-to-peer, which means a lot less than 12-13% of people who got the album paid for it. On the positive side, the expensive $300 and $75 packages helped offset the large majority who paid nothing, and selling directly to fans let them skip the record-label middleman – letting them reap more revenue per sale. Although, it would be a false dichotomy to say that NIN only had two choices: the record labels or free/creative commons. A third alternative would be to simply sell the album from their website (without putting it under creative commons, and without putting it on bit-torrent).

It’s true that he did “allow” it to be shared, and that he uploaded it to bit-torrent himself – which seems to suggest that he believes that “giving it away for free” doesn’t hurt sales. On the other hand, NIN didn’t make it easy or obvious to download the entire 36-track album from their website. This made it difficult for anyone without bit-torrent to get it for free. My take on this behavior is that Trent Reznor doesn’t try to stop filesharing because it’s going to happen, but he also doesn’t want to make it easy for non-bit-torrent / non-pirates to download his music for free. I can understand the logic of this. Afterall, the music would be leaked to bit-torrent regardless of NIN’s stance on the issue. And people who torrent wouldn’t be swayed by Reznor’s appeal to not pirate his music, anyway. Since he has zero control over piracy, he might as well try to make some friends and get free publicity by taking a controversial stand.

It would be nice if we could generalize his experience to other bands / companies. But, there’s obviously a number of complications in trying to do that.

I suppose some of the lessons or non-lessons might be:

– Sell physical products with tiered pricing. This way, your biggest fans can pay you $75 or $300. Unfortunately, this only works for bands with a strong following; most bands aren’t going to get very far selling $300 packages. But, there might be other tiered pricing that works – like $10 / $20 / $30.

– Publicity stunts like releasing music under creative commons or making it available on torrents might get you some media attention. Unfortunately, this only works with bands that can already garner news media attention. No one cares if the local band has gone creative-commons.

– Selling directly to fans lets musicians get a bigger cut of each sale. But, this strategy involves forgoing the record-label’s publicity machine. NIN already has enough fame that “more publicity” has limited value.

– Even if you eliminate all the “barriers” that most people cite for pirating music (including: DRM, don’t want to pay the evil record labels, the musicians don’t make money from music sales, lowering prices down to a ridiculously low $5 for 36 songs), most people still aren’t going to pay you if you give them a free option. The percent who pay will probably vary depending on how much people like the music, but if NIN is getting fewer than 1 in 8 to pay anything (and numbers are a lot lower if you include torrents), I think things look rather dismal. On the other hand, we have no idea how many of those “free download” people even liked the album or would’ve bought it.

– Even Trent Reznor seems to agree that making it easy / convenient for non-pirates to download your music for free probably hurts sales. On the other hand, releasing it for free on bit-torrent probably doesn’t hurt you much because it’s going to be there regardless of what you do, and people using bit-torrent are going to pirate music anyway.

Doom 1 in Flash

Wow, you can play Doom 1 online.

Controls:

W, A, S, D or ARROW KEYS – movement

Q, E – strafe left, right

SPACE – fire

R – use door/switch

SHIFT – run

ESCAPE – menu

TAB – map

NUMBER KEYS – change weapon

Click on the image to play it in a popup window:

I forgot how hard it is to play first person shooters with the keyboard. And I forgot how old it is. Considering that the game is 15 years old, it’s graphics are surprisingly good.

Astroturfing

A couple of days ago, one of Belkin’s reps got caught trying to hire people to write good reviews of their products. Given the spate of fake reviews and other games (see my earlier post about Eidos manipulating journalists), it’s not only clear that companies have an incentive to mess with reviews and create fake “user” reviews, but it’s happening. Like everyone else, I don’t like these types of tactics. I’m a consumer just like everyone else, so I don’t like it from that perspective. It’s dishonest and manipulative. Secondly, I don’t like it as a game developer because it undermines trust in the whole game-review process. I usually check reviews before buying a game or product, and if I think some of the reviews are fake, I’ll have less trust in positive reviews. As a result, I’ll be less likely to accept positive reviews – which leads to the reaction that I’m less likely to buy. In other words, fake reviews have the ultimate effect of hurting sales of good products. And, if you’re a company who doesn’t create fake reviews, well, users don’t know it and your reviews end up being lower than numbers for comparable products (because they’re padding their numbers).

It sort of makes me wonder if companies would go out of their way to make fake reviews of their competitors’ products.

Some other examples of fake “reviews”:

I happened to see some videos on GameTrailers.com for a game called “Rat Race” a few months ago. I think many of those votes are fake. First, I think they’re fake because they are remarkably positive for some bad video clips (could anyone really believe user votes are in the 7.1-8.5 range)? And secondly, if you compare the number of votes and comments to the number of views, they are remarkably incongruent. Specifically, they have five videos up. Here’s the numbers:

| Video | Number of Views | Number of Votes | Number of Comments |

| 1 | 78,413 | 598 | 199 |

| 2 | 45,600 | 513 | 173 |

| 3 | 40,094 | 474 | 171 |

| 4 | 21,617 | 501 | 189 |

| 5 | 30,785 | 509 | 196 |

Notice anything odd with those numbers? How about this: video #1 has almost four times as many views as video #4, but all the videos have almost the same number of votes and comments. Hmmm. Okay, I can’t expect the ratio of views-to-votes to be exactly the same, but it just seems suspicious.

A while back, Penny Arcade also had a comic about getting paid to write fake user reviews. I can’t find the exact post, but Gabe and Tycho said they discovered the existence of third-party companies who hire people to travel around the internet writing fake reviews for companies that hire them.

And, there was also that Amazon glitch a few years ago that accidentally showed the reviewer’s real names on the website. Authors were caught writing glowing reviews of their own books, but pretending to be someone else.

And, of course, there was a whole bunch of shadiness around Kane and Lynch. For example:

When viewing the official Kane & lynch website, a flash ad comes up with two 5-star reviews which… well… which don’t exist:

GameSpy did not say “It’s the best emulation of being in the midst of a Michael Mann movie we’ve ever seen” in their review of the game. They said that in their E3 2007 coverage. In other words, a preview. They also did not give the game five stars. They gave it three.

As for Game Informer, same deal. The highlighted quote does not appear in the review of the game. Nor do they give it five stars. Game Informer don’t even score in stars. They gave it a 7/10. (Source)

And I’ve heard that movies have a similar phenomena: there are certain people you can always count on to give a positive review. The movie companies know who they are, and then use them in their advertising, so they can say stuff like “a roller-coaster thrill ride! five stars!”. At least in that case, the “review” is part of the advertising, so we know not to trust it.