I recently stumbled on a recent news article claiming that, according to a Norwegian study of music-buying habits, people who pirate music buy ten times as much music as people who don’t.

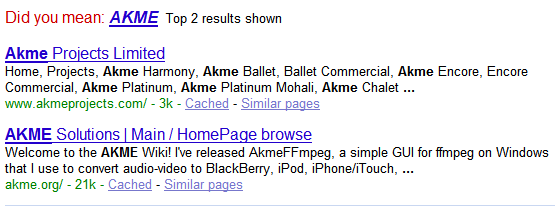

I’ve also seen a similar study done in Canada. I haven’t had a chance to delve into them too deeply (though the Norwegian one doesn’t seem to be available in English, anyway). A quick google search reveals that a lot of pro-filesharing websites are praising the results, but I’m skeptical.

The first questions I think when I read about these types of studies are:

– “Did researchers rely on pirates self-reported music purchases?” and

– “Did pirates feel increased pressure to purchase music when they knew their actions were being recorded by researchers?”

According to the write-up, “the study did not rely on music pirates’ honesty. Researchers asked music buyers to prove that they had proof of purchase.” Sounds good, although I’d wonder if all of them had proof of purchase, and how the researchers treated the case where they didn’t have a receipt.

Another possibility is that a portion of pirates are pretending to be non-pirates – either for legal reasons or because they’re saying what is most socially acceptable. (Many social scientists are very skeptical about self-reported numbers when a behavior is not socially acceptable.) If a pirate never buys anything, but masquerades as a non-pirate, it lowers the apparent music-purchasing numbers of non-pirates relative to pirates. On the flip-side, the pirates who “try before they buy” feel more justified in admitting their piracy since they also buy a great deal of music. This would create the appearance that the average pirate is more likely to buy music than is actually true. There is good reason to suggest that this is going on. According to a recent Dutch study, 93% of Dutch people between the ages of 12-24 admit to downloading music, movies, or software. And another study says “81% of Spanish Internet users under 24 download copyrighted content via P2P files.” On contrast, the Norwegian study says only 40% of Norwegians between the ages of 15-20 admit to “free downloading”. Why is there a 53% gap between the Dutch and Norwegians? Maybe this is explained by Norwegians claiming not to pirate when they actually do. If we were to mix-together the Dutch and Norwegian numbers (questionable, I know, but this scenario is theoretically possible), all this study is comparing is music purchases by people who admit to piracy (40%) compared to music purchases by people who don’t admit to piracy – which is mostly pirates (53%), but also a small section of people who aren’t pirates (7%). (Even worse, the Norwegian study didn’t ask about “piracy” specifically, but they asked whether or not people had taken “free downloads” – meaning that 40% might include non-pirates.)

And a fourth possibility is that piracy and music purchases are both correlated with wealth. In other words, if you have wealth, you are more likely to have a computer (which you need for piracy) and you are more willing to buy music (because you have plenty of extra money). Less-wealthy Norwegians, on the other hand, might be making cassette tape/CD copies of music, but aren’t pirating off the internet, and they aren’t buying much music. This situation would create a correlation between piracy and purchases, but would invalidate claims that ‘piracy drives purchases’.

I did notice one odd thing in the news article. Early in the article they say:

A report from the BI Norwegian School of Management has found that those who download music illegally are also 10 times more likely to pay for songs than those who don’t.

But, a few paragraphs later, they say:

Researchers found that those who downloaded “free” music – whether from lawful or seedy sources – were also 10 times more likely to pay for music.

Wait – free music from lawful sources? I’ve downloaded free music from lawful sources. I’ve downloaded free albums from band’s websites. I’ve downloaded free songs from MySpace (when they have the little “download” link). I’ve downloaded free songs using those little Starbucks / iTunes promotional cards. I do not pirate. Apparently, I would be included in the group of “those who downloaded free music” – which some people are interpreting as “pirates”. So, my music purchases would be included in that “music purchases by pirates” group. I’m not at all surprised that people who downloaded free, legal music would purchase more music than people who didn’t. Afterall, people who download music (legally or illegally) are more likely to be “big music fans” than people who don’t, so I would expect a correlation.

There’s several reasons I don’t trust these studies:

(1) It doesn’t fit my personal experience of how pirates operate. I know a few people who pirate. If you told them to pay for some digital content, they’d look at you like you bumped your head and forgot that they have this awesome thing called piracy. On different occasions, I’ve seen two of these pirates chide other people for buying things that could be pirated. Clearly, they aren’t the “buying” type of pirates if they complain when other people buy digital media. [June 9, 2009 Update: According to this BBC article, the British Phonographic Industry is quoted as saying “The consensus among independent research is that a third of illegal file-sharers may buy more music and around two thirds buy less.” This pattern would, at least, confirm my observation about many pirates refusing to pay for digital content. I have to wonder about the other one-third. Are they using piracy merely as a “try before you buy” service, but trying to follow the spirit of the copyright laws? I think that’s possible. At the same time, if that interpretation were true, then it would suggest that they might act differently in a world with legalized filesharing – which is something that some anticopyright activists are pushing for. It’s likely an incorrect assumption that pirates today behave similarly to the way people would behave if filesharing were legal.]

(2) One of the common reasons people on the internet give for piracy is that they are poor. If someone is poor, they aren’t likely to pay for the stuff – especially if they’ve already pirated it. Other pirates complain that music companies or musicians make too much money, they hate DRM, or they’re sticking-it to the nasty record companies who are evil because they sue pirates or pay the musician pennies per sale. I even saw one pirate claim that people pirate as an act of “civil disobedience” against unfair copyright laws. People using those explanations for their piracy don’t sound like people who turn-around and buy music. So, when this Norwegian study says the average pirate buys ten times as much music as non-pirates, I’m skeptical. It would be interesting to see the detailed information about this. Maybe half of all pirates never pay for anything, and the other half actually do buy stuff. In this case, the average “buying” pirate would have to purchase 20x as much stuff as the average non-pirate. That seems like a stretch, but at least that explanation would confirm my own observations about the existence of non-buying pirates while also allowing the study to be right.

(3) Music sales have been on a downward trend for the past eight or so years. Now, there may be plenty of factors involved, but they’re down something like 40% compared to the year 2000. In Spain, where filesharing is legal, music sales dropped 56% between 2001 and 2008. Piracy might only be part of the explanation for that decline, but let’s say that piracy increases music sales (i.e. piracy increases sales, rather than piracy is correlated with sales). This means music sales are down 40% (or 56%) despite sales-increases due to piracy? That seems unlikely. Afterall, if we assumed an increase in piracy of only 10% (for example, from 20% to 30% of the population), and we believed that piracy increases sales by 10x, then a 10% increase in piracy should result in nearly doubling total music sales. Instead, we see things going in the exact opposite direction.

So, I’m still doubtful about the result that pirates (on average) buy 10x as much music as non-pirates. I also have to question whether or not these studies are done accurately and honestly (by both research subjects and researchers themselves). Afterall, South Korean scientists have faked their results. Piracy is a contentious issue, and I wouldn’t doubt that people would fabricate results. Another possibility is that some biased news reporter is twisting the results to say something that they didn’t say. And since the original results are in Norwegian, it’s hard to verify the actual results.

Links to the Norwegian sources (translated by google):

BI Norwegian School of Management

Norwegian News

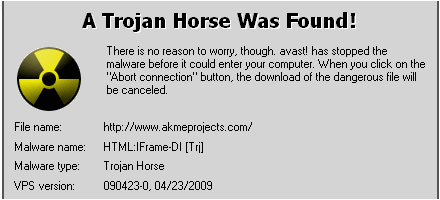

.jpg)