Wow. This is quite a trailer:

Category Archives: Games

Bad AI

I had to laugh at these videos.

They’re from Cracked.com’s “5 Things The Gaming Industry Will Never Fix (And Why)”.

iPhone Development

I’ve been asked a few times about whether or not I’ll create iPhone applications. I haven’t looked into it much, prefer desktop/laptop development, and generally feel that the iPhone “gold rush” is over anyway. I think there was a time, a few years ago, when you could get a big benefit by being the first one there. But, everyone noticed the opportunity, and now there’s lots of competition. From what I can tell, there are a few success stories, and the vast majority of iPhone apps languish in obscurity.

Here’s two contrasting articles. The first one is written from the user’s perspective. You’d get the impression that iPhone development is a gold-mine. But, of course, he only mentions the most popular applications:

Last month, I became an obsessive air-traffic controller. The culprit: a terrific game for the iPhone called Flight Control. The premise is simple: You’re faced with a crush of planes, and it’s your job to guide each one to its respective runway…. According to Firemint, the game’s publisher, the 99-cent app has been purchased more than 700,000 times since March; at its peak, it was being downloaded 20,000 times a day.

…

Last fall, [Ethan Nicholas] spent weeks—some of it while cradling his 1-year-old son—writing a tank-war game called iShoot. The game, which sold for $2.99, hit the App Store in October, and in January, it shot up to the top spot—selling hundreds of thousands of copies and earning Nicholas enough to let him quit his job and take up iPhone development full-time.

Source: Slate

The second article is about iPhone development from a software-developer’s perspective. It isn’t the gold-mine you’d think it is. There are 40,298 applications for the iPhone. The author does some estimates to figure out the average profitability of an iPhone application (about $1,881). At that amount, you’d better be cranking out a decent application every month to earn a bare-minimum living ($22k/year). Of course, there’s a lot of variability in this: some huge successes and lots of applications that earn next to nothing. So maybe “average” isn’t the best way to look at this. Afterall, if you have 70 applications that earn $1 million each, 2,000 applications that earn $1000, and 38,228 applications that earn $100 each, you’d end up with his same numbers. It would look more like a lottery under these numbers – almost everyone would end up poor, and a handful of people would get rich. These same numbers would also produce a bunch of “success stories” – 70 of them – that the media could write about, as if the iPhone was a sure-way to quit your day-job and earn a great living.

From what I hear, the top-selling applications tend to get a boost by getting onto Apple’s Top 10 list, and (to a lesser extent) the Top 50 list. Again, this suggests that there are some big winners, and a lot of losers.

Update, June 9, 2009: It’s nice to get a little confirmation of my view. In a recent blog post, iPhone developer Rick Strom says:

First, so you know where I stand among the 60,000 or 600,000 (I’ve heard both numbers) registered iPhone developers: I have nearly 20 apps in the app store as of this writing.

Four of those apps are on the charts:

* Zen Jar #34 Social Networking (paid)

* Zen Jar Lite #54 Social Networking (free)

* Spirit Board #36 Board Games (free)

* Spirit Board Pro #95 Board Games (paid)

…

With two apps on the [Top 100] paid charts, one would assume I’m rolling in dough. After all, this is a gold rush, right?The reality is much more startling. In order to place #34 on the social networking charts, you need 30-35 downloads a day. At the standard app store pricing of .99, and after Apple takes its cut, that means your app needs to bring in a little over $20 a day to chart at that position. And social networking is a popular category.

Perhaps you’d expect the game charts to do better. Board games isn’t a wildly popular category, but it still might surprise you that it takes about 6-8 downloads a day to chart. That means if you are making around $4 a day you’ll be in the top 100.

So what does this all mean? Well keep in mind there are over 36,000 apps in the app store. If the apps on the category charts are doing those sorts of numbers, what do you think the rest of them are doing?

Nothing. Absolutely nothing. The aren’t selling at all.

…

I post these numbers so people can understand what is really involved here. The app store isn’t a sane marketplace at all, any more than the lottery is. When you submit an app, you are buying a ticket. Maybe you will be one of the few who makes a couple hundred grand in a hurry, but most likely you will be just another shlub tossing your blood, sweat and tears into the void where it will be ignored.

Free Doom / Hexen / Heretic

Free Flash-based versions of Doom, Hexen, and Heretic. Play them here. (Hmm, reminds me of college.)

Shadow Physics Game Video

Here’s an interesting little game from the Indie Game Developers Conference. Admittedly, he got some of his ideas from Crayon Physics (download the demo here). I’m not sure that I like some of his more complicated ideas at the end, but it’s an interesting game idea.

[Source: todaysbigthing]

Art Inspired By Games

PixelJunk 1-4

PixelJunk 1-4 looks like an interesting little shooter. Apparently, they’re also looking for a name.

Braid

.jpg)

I downloaded the Braid demo the other day. I have to admit, despite all of the buzz I’ve heard, I’m not really that impressed. I have to give him points for some interesting game dynamics. The artwork and the audio was interesting and unique, but I didn’t really feel compelled to keep playing it. It just didn’t grab me. You can grab a copy for yourself here. Maybe you’ll feel differently.

Indie Game Developer

Here’s an interesting post by an Indie Game Developer:

So Here’s How Many Games I Sell.

I get a lot of questions from young, aspiring Indie developers, and the most common query is: How many copies of a game does Spiderweb Software sell? It’s a really reasonable question. After all, making a game is a long and punishing process. It’s entirely fair to want to know what the parameters of success are. Alas, this information is generally kept secret. I’ve never given this question a straight answer, with real numbers.

Until now.

…

( read the rest of the article on his website )

Gabe Newell (Valve) and the Game Industry

A few news articles have been coming out of the DICE Summit. In an article titled, “The Very Different Gaming World Gabe Newell Wants”, Newell had some thoughts on “how he thinks the video game industry should work”.

-Pricing that’s always in flux: Are you ready for the price of a game to go up and down regularly? “One of the things that annoys me is the inefficiency in pricing we have in our industry,†Newell said. He doesn’t like how rigidly prices are set in stores and how slowly those prices are changed… Valve has hired an experimental psychologist to concoct new sales promotions, one possible idea being to reward every 25th purchaser of “Left 4 Dead†with a free game on Steam. Newell joked that this person is “turning us to the dark side of B.F. Skinner.â€

Hm. I’m not sure that I’d categorize this under “how the gaming industry should work”. I think what Valve is doing with the price fluxuations is this: attract attention. By having sales, they have an excuse to get into the gaming news. They also give people a reason to keep checking their website (any sales yet)? If you can keep people coming back to your website, odds are better that they’ll buy something – maybe even buying/trying a different product from Steam. As far as I can tell, it’s worked pretty well. I saw gaming websites talking about Valve’s “Left 4 Dead” sale. For example, Joystiq posted this article: “This weekend: Left 4 Dead 50% off on Steam”. Price fluxuations = excuse for gaming websites to talk about you = free advertising.

-Frequent content updates: Newell said “Team Fortress 2″ has received 63 updates from Valve in the last 14 months. That is the future, he told the developers in the audience: “You’re going to be touching [your customers] not every three years but every three weeks — and hopefully even more often than that.

Wait – this if how the gaming industry is supposed to work? If you do the math, there, you’ll see that 63 updates in 14 months is more than one update per week. One of my irritations with Team Fortress 2 was that they were always updating it. Want to play a quick game before you go to bed? Oops! You have to download a patch before you play. Hope you don’t mind a 20 minute download first. One of the other problems that happens with PC games is that the ability to patch games after release means developers feel less bad about releasing a “not quite complete” games, knowing that they can patch it after the fact. One guess here is that Gabe wants to make sure people are tied into the Valve service (since patches are only available through your account) – which means you bought your game (and didn’t pirate it). Frequent updates means pirates are running old versions, and if you want the latest fixes, you’d better buy it. It certainly keeps the uploading-pirates and downloading-pirates busy. I’m doubtful that it improves anything for gamers, but if it helps Valve shake-off some pirates and get some more sales, then gamers are helped indirectly.

-Video game companies acting as “entertainment companiesâ€: Newell said he is “obsessing†over gamers’ expectations for “what kind of entertainment company they want us to be.†They are fans of properties, not forms of entertainment, fans, to use his example, of Harry Potter, as opposed to just Potter books or just Potter movies. As a result, he said he is moving away from thinking of Valve as a video game company. One example is the introduction of “Team Fortress 2″ video shorts made by Valve. The next will be that same team’s “TF2″ comics.

Selling merch – aka: opening up another revenue stream for the company. Not a new idea, but not a bad idea, either.

-No DRM should be offered that can be thought of as DRM: Newell believes that digital rights management software that is presented as copy-protection gives a game a stink. It leaves customers unsure about how flexibly they can access their games. So they turn to pirates who offer games with fewer strings, he suggested. “There is evidence anecdotally that DRM is increasing piracy rather than decreasing piracy.†Valve’s solution: battle the pirates by providing better services than the pirates do. The effectiveness of pirates, he said, is to get content to people who want it more swiftly and easily than the companies who make the content do. An outfit like Valve, however, can get provide even better service, even by doing something as intrusive as data-mining their customers’ computers — as long as they are transparent about it and can prove to the customer that taking such measures will make the customers’ games better.

Well, this isn’t really news coming from Valve. I’m always amused when people rail against DRM, but then suggest following in Valve’s footsteps (oblivious to the fact that Steam is DRM). What this says to me is that there is a right way and a wrong way to do DRM – which is different than view promoted by groups like DefectiveByDesign: that all DRM is bad – inherently wrong, wrong in principle. Ideally, gamers should be able to use their games (and music and movies) without ever running into restrictions during normal use. At the same time, Steam is there to stop people from uploading/downloading games to filesharing sites. Gabe Newell is frequently misunderstood when talking about DRM. You often have to parse his words very carefully to understand exactly what he means. For example, Joystiq paraphrases him as saying “Gabe Newell wants to shake up the way the industry works by … getting away from DRM as copy-protection”. That sentence sounds like Newell is opposed to DRM. He’s not. The original article quotes him as saying: “Newell believes that digital rights management software that is presented as copy-protection gives a game a stink.” Newell is suggesting digital rights management that isn’t presented as copy-protection – it’s presented as a system to automatically download patches, etc. In an article less then six months old, Doug Lombardi (of Valve) was quoted as saying:

Lombardi, and others I spoke to off the record, say that at least for digitally downloaded PC games, DRM and copy protection is here to stay. For Valve the biggest push is to lock down those “zero day” pirates. Day zero is the time between when a game goes gold and when it is available for purchase… The key to making a good authentication system, Lombardi says, is to not stand in the way of customers enjoying what they bought.

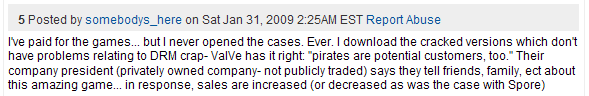

By keeping their DRM strings invisible, many gamers seem unaware of the fact that Steam is DRM. I see examples like this all the time:

Valve seems to have managed to simultaneously use DRM and get lots of people to praise them for not using DRM. And, of course, if people break their DRM – well, Valve can fall-back on the fact that only legitimate buyers get the weekly updates mentioned earlier.

-Concept art for everyone: Newell wants creators and customers to be in more direct communication with each other before and after the release of a game. One such method is to show concept art early, which builds buzz. The concept art, Newell said, “is a more effective tool [for building buzz] than most of the advertising around your product.â€

This idea isn’t even remotely new.

It won’t be better graphics that determines a winner in the next console generation (which, of course, it never has been: see the N64, Xbox and PS3). It’ll be the extent to which a console allows game creators “to have this relationship with your customers.†The “this†is everything bullet-pointed above.

True. You want customers coming back to your website over and over. I’m sure the Valve-customer relationship will establish their website as great place to advertise their next game, increase brand recognition, open up more possibilities for selling old stuff / merch, becoming more than just a faceless corporation, etc, etc. The other day, I was thinking about how the games industry is different than a lot of other industries. I don’t really remember what companies made which games, and which games were made by which companies. It’s just not that important because titles are so variable. I’m never in a position where I say, “Oh, Valve made X. I like that game. Here’s another game by Valve. I’ll probably like this one, too.” But, when I’m talking about a musician or an author, I think it’s a different situation – I might buy an album from a musician if I like their other stuff, even if I haven’t heard a single song from that album. And people have a pretty good idea what a book will be like if it’s written by Stephen King. But, we just don’t follow game companies like that. Maybe games are more variable in their execution. What this ultimately means for game companies is that they have to convince customers of the merits of each and every game (rather than relying on an “established reputation”). The relationship Gabe is talking about plays an important role in selling the merits of the next game.

In the end, I don’t think Gabe Newell has much new to say, and it certainly isn’t a “very different gaming world” (as the title of the article suggests). One thing that did occur to me while reading this, though, is that the gaming industry is picking up the same strategies that politicians have used on the campaign trail: repeat yourself constantly. Repeat, repeat, repeat – drill in your ideas over and over because different people are listening each time. It seems like the game companies maintain a set of talking points – stuff they can repeat to game journalists for a story. (I remember Brad Wardell of Stardock doing the same thing.) I hope I never have to play that role. I get really bored of repeating myself.