I’m always kind of curious about the results when companies try different business strategies. Nine Inch Nails released their last two of their albums for free. Well, free if you wanted them for free. Anyone can download The Slip off of their website for free. You can get the first nine songs of Ghosts I-IV for free. If you want the other 27 songs, you can get them a few different ways: free, $5, $10, $75, or $300 – depending on which package you want. (The packages at $10+ contain various physical media, including DVDs, Blue-Ray with surround sound, etc.)

When they first did this, I wasn’t quite sure about his motivation, but I can imagine a whole bunch of possible motivations – to drive up concert sales, as charity to the fans, faith that fans would pay, etc.

I’ve seen a number of people use the NIN experiments as evidence that giving away music “works for musicians”. In many cases, this is part of a “piracy doesn’t hurt anyone” or “this shows that creative commons works” kind of an argument. For example, RollingStone says: “it proves — along with Radiohead’s chart-topping success of the physical release of In Rainbows — that music fans are willing to support artists even if their music is offered up at no cost.” And Ars Technica: “Nine Inch Nails’ Ghosts I-IV topped Amazon’s digital download charts in 2008, despite being offered to fans free of charge. Creative Commons touts the project as a new model for music… The next time someone tries to convince you that releasing music under CC will cannibalize digital sales, remember that Ghosts I-IV broke that rule, and point them here.”

I’m less certain about the success of these experiments. Here’s the results: NIN Ghosts I-IV was the number one downloaded album on Amazon’s 2008 charts, and brought in $1.6 million in revenue within the first week of sales. Sounds good. But, let’s break down those numbers.

They sold Ghosts I-IV in a few different formats. First, you can download the first 9 tracks for free off their website. All 36 songs are available for free on filesharing networks. Even though it was released it under Creative Commons for free, Trent Reznor didn’t make it too obvious and doesn’t provide a link to download all 36 songs. It appears that most people didn’t know that the full album was available for free. And even if they did know it was free, they wouldn’t know how or where to get it anyway. It’s also available in $5, $10, $75, and $300 Ultra-Deluxe packages. We know that there were 2500 copies sold of the $300 packages. (It pays to have rabid fans.) But we have to guess on the rest. We also know that there were “781,917 transactions“. Obviously, “781,917 transactions” includes people who downloaded the 9 free songs (if it only included actual sales, then 781,917 transactions would be a lot more than $1.6 million).

Here’s what I think is a reasonable guess of sales for the first week:

$300 package x 2,500 copies sold = $750,000

$75 package x 5,000 copies sold (just a guess) = $375,000

$10 package x 10,000 copies sold (just a guess) = $100,000

$5 package x 78,884 copies sold (just a guess) = $394,420

Free download x 685,533 people (88% of the transactions)

——————————–

Total Transactions = 781,917 (the number given to us from this article)

Total Revenue = $1,619,420 (the number given to us from this article)

Now, under these numbers, about 12% or 96,000 people bought something. (If no one bought the $75 or $10 packages, then $5 sales would be at 174,000 copies.) About 700,000 people downloaded the free 9-song version, and who knows how many people downloaded all 36 songs via peer-to-peer networks.

I think one lesson that can be learned is that tiered pricing a big benefit to bands with rabid fans. Most bands couldn’t get away with a $300 package, but (based on my guesses) NIN made 70% of their money from the $300 and $75 packages.

But, I was also surprised by the low number of purchases. Fewer than 100,000 people bought something. Okay, so this is only the first week of sales, but in 2005 (less than a month after their fifth album was released) NIN claimed to have over 20 million albums sold worldwide, which means an average of 4 to 5 million copies sold per album. Additionally, with 800,000 downloads, it means that 7 out of 8 people downloaded the free version and didn’t buy anything. Of course, this makes me question Ars Technica’s conclusion that “[Creative Commons won’t] cannibalize digital sales”.

As far as being the number one downloaded album on Amazon in 2008 (which is based on the entire year, not just the first week’s sales), it looks like NIN routed all their $5 sales through Amazon.com as mp3 downloads. Since Amazon doesn’t have strong mp3 sales in general and all of the $5 sales went though Amazon, and the fact that competing music was split between physical media and downloads as well as being available at a variety of stores, then maybe it’s not surprising that they placed so high in Amazon’s best-selling mp3 list. Digital music downloads are still dwarfed by physical-music sales, making up only 10-20% of total music sales. Given these facts, “#1 downloaded album on Amazon in 2008” is a little less impressive than it sounds.

So, was Reznor’s experiment a success? Does this vindicate Creative Commons as a viable and reasonable alternative to selling music? I’m doubtful. It seems like Reznor has mixed feelings. In an interview done last year (before releasing Ghosts I-IV) Reznor talked about his collaboration with Saul Williams. They put an album together and released it as both free download and as a $5 purchase:

Reznor produced and helped bankroll the album, which debuted November 1. All the more reason why he was stunned when fewer than one in five people who downloaded the music were willing to pony up $5, roughly the cost of a McDonald’s Quarter Pounder.

…

Reznor ended the hoopla last week when he reported on his blog that 154,449 people had downloaded NiggyTardust and 28,322 of them paid the $5 as of January 2. In the blog, Reznor suggested that he was “disheartened” by the results.

…

[Y]ou have a lot of reasons why you [don’t want to buy music from the record labels]. So I thought if you take all those away and here’s the record in as great a quality as you could ever want, it’s available now and it’s offered for an insulting low price, which I consider $5 to be, I thought that it would appeal to more people than it did. That’s where my sense of disappointment is in general, that the idea was wrong in my head and for once I’ve given people too much credit.

Saul and I went at this thing with the right intentions. We wanted to put out the music that we believe in. We want to do it as unencumbered and as un-revenue-ad-generated and un-corporate-affiliated as possible. We wanted it without a string attached, without the hassle

…

I’m not saying it was a failure or a success. I think it was both. But it wasn’t 90 percent of the people that showed up paid us what we asked for. Nor did I ever think it would be. I’m not sure what I did expect.

But I’ve found it entertaining reading different people’s perspective on the Web, what they’ve thought of what I’ve said. There’s been a wave of people that said, ‘Oh, that’s depressing. Only 18 percent chose to pay for it.’ Another whole wave of people feel just the opposite. I don’t really know.

CNet News: Trent Reznor: Why won’t people pay $5?

Now, looking at the downloads versus purchases of Ghosts I-IV, we can say that only about 12-13% of the people paid $5 or more for the 36-track album (as opposed to downloading the free 9-tracks from the NIN site). Additionally, a lot of people got the music via peer-to-peer, which means a lot less than 12-13% of people who got the album paid for it. On the positive side, the expensive $300 and $75 packages helped offset the large majority who paid nothing, and selling directly to fans let them skip the record-label middleman – letting them reap more revenue per sale. Although, it would be a false dichotomy to say that NIN only had two choices: the record labels or free/creative commons. A third alternative would be to simply sell the album from their website (without putting it under creative commons, and without putting it on bit-torrent).

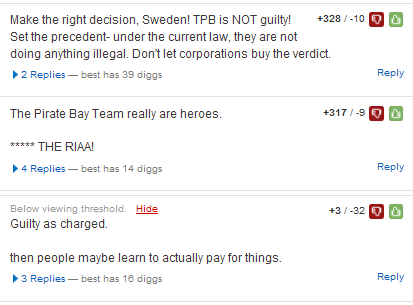

It’s true that he did “allow” it to be shared, and that he uploaded it to bit-torrent himself – which seems to suggest that he believes that “giving it away for free” doesn’t hurt sales. On the other hand, NIN didn’t make it easy or obvious to download the entire 36-track album from their website. This made it difficult for anyone without bit-torrent to get it for free. My take on this behavior is that Trent Reznor doesn’t try to stop filesharing because it’s going to happen, but he also doesn’t want to make it easy for non-bit-torrent / non-pirates to download his music for free. I can understand the logic of this. Afterall, the music would be leaked to bit-torrent regardless of NIN’s stance on the issue. And people who torrent wouldn’t be swayed by Reznor’s appeal to not pirate his music, anyway. Since he has zero control over piracy, he might as well try to make some friends and get free publicity by taking a controversial stand.

It would be nice if we could generalize his experience to other bands / companies. But, there’s obviously a number of complications in trying to do that.

I suppose some of the lessons or non-lessons might be:

– Sell physical products with tiered pricing. This way, your biggest fans can pay you $75 or $300. Unfortunately, this only works for bands with a strong following; most bands aren’t going to get very far selling $300 packages. But, there might be other tiered pricing that works – like $10 / $20 / $30.

– Publicity stunts like releasing music under creative commons or making it available on torrents might get you some media attention. Unfortunately, this only works with bands that can already garner news media attention. No one cares if the local band has gone creative-commons.

– Selling directly to fans lets musicians get a bigger cut of each sale. But, this strategy involves forgoing the record-label’s publicity machine. NIN already has enough fame that “more publicity” has limited value.

– Even if you eliminate all the “barriers” that most people cite for pirating music (including: DRM, don’t want to pay the evil record labels, the musicians don’t make money from music sales, lowering prices down to a ridiculously low $5 for 36 songs), most people still aren’t going to pay you if you give them a free option. The percent who pay will probably vary depending on how much people like the music, but if NIN is getting fewer than 1 in 8 to pay anything (and numbers are a lot lower if you include torrents), I think things look rather dismal. On the other hand, we have no idea how many of those “free download” people even liked the album or would’ve bought it.

– Even Trent Reznor seems to agree that making it easy / convenient for non-pirates to download your music for free probably hurts sales. On the other hand, releasing it for free on bit-torrent probably doesn’t hurt you much because it’s going to be there regardless of what you do, and people using bit-torrent are going to pirate music anyway.