The Cost of Digital Content Creation

The main reason I support copyright is because of the effort and costs associated with creating digital media, and the need to pay-off those costs.

Copyright gives the public an incentive to pay for the digital media (if you don’t pay, you don’t get the product; if you do pay, you get the product). If the public can get the product for free, then there’s little incentive to pay. (I deal with alternative revenue systems in another post.) Collectively, the public then helps the creator pay-off the costs of development. The model looks something like this:

Step 1: Work hard to create a product. This could take thousands of hours of work or involve paying other people (employees or third-parties). Bills will pile up during this time. Personally, I spent over $100,000 (mostly in living expenses, while living cheaply) while creating my software.

Step 2: Product Release: You’ve wracked up a lot of debt and now you try to sell your product to the public. (For example, maybe you’ve accumulated $2 million in debt to create the product. At the moment, you are $2 million in debt and you’ve earned zero money to pay-off that debt.)

Step 3: The public pays small amounts of money ($1, $20, or $50) to buy your product, enabling you to first pay-off your debt via lots of small, individual payments. (For example, maybe you earn $10 for each copy sold, now you need to sell 200,000 copies to pay off your debt – i.e. to break even.) If you’re a small-time creator, this is what determines whether you earn $1/hour or $10/hour for the labor you did in step 1.

Step 4: If you make a good product and it sells well, hopefully you’ve made enough money to pay-off your debts, and you can make a profit for your work. (Congrats. Take a vacation, take a raise, expand your business, hire more workers, fund your next project, pay-off debts from your last failed project, etc)

Many companies have a hard time getting to Step 4. I’ve heard it said that most small software companies are always one bad project away from bankruptcy.

What piracy does is allow the public to skip out on Step 3 and 4, which leaves the creator in debt (and soon to be bankrupt) while they get free copies of his work. “Sharing” is really about skipping-out on helping the creator pay-off the development costs. Many pirates will complain that they aren’t taking anything away from the creator by getting free copies, but this ignores the fact that the creator is in the bad position of needing to pay off huge creation costs. In other words: if you have a debt of $2 million, and everyone in the world feels that they aren’t “taking anything away from you” by getting free copies of your work, then you end up with $2 million in debts and $0 in revenue to pay-off your debts. What this teaches creators is: “Don’t make stuff. Even if people like it and benefit from it’s existence, you’ll still go bankrupt”.

Pirates will try to cast creators as evil for suggesting that people shouldn’t “share” (what cartoonish villains we must be for telling people not to share), but once you understand the economics of the situation, you can see the problem.

This is why I support copyright: because there is a need to pay-off the development costs and create incentives for the creation of new digital media. If creating new digital media took 30 minutes of work or if it fell from heaven into our laps, I’m inclined to say that everyone should give it away for free. But, we’re talking about enormous amounts of money, effort, and time (and time is money), so it’s important to create an economic system to support and reward the creations of new works. We wouldn’t expect to have a decent healthcare system if we expected doctors and nurses to work for free, and we shouldn’t expect a decent amounts of digital media to be created without paying creators for their labor, either.

There are, of course, alternative funding models, though none that I think work particularly well. (I’ll deal with these later.) My own personal opinion is that the ideal model is one where creators give away their creations for free and the public responds by generously donating to them. This way everyone wins: the public gets free access to everything, and creators get paid for their work, which also enables them to keep creating. Unfortunately, I don’t believe that the public is that generous, so incentive-based systems like copyright have to be created. (Copyright is an incentive or trade-based system because it says, “You can get the benefits of this product if and only if you give me the benefit of your money.”) The worst system is a situation where creators give away their work freely (or have it taken via piracy), but society doesn’t pay or infrequently donates, leading to bankruptcy for creators and a collapse of the financial system that supports the creation of new works.

Fairness

Because of the large upfront costs that are paid-for by the creator (or publisher or other investor), it only seems fair that a creator be allowed to require that users (who get the benefits of the creation) pay a fee to use the it. I think there are comparisons that can be drawn to other business models that involve large upfront costs and low per-user costs. If we allow those businesses to operate on their own terms, then we should allow copyright industries to do the same.

One example I sometimes think of is this: imagine that you and two friends are taking a trip down to Florida for spring break. Let’s say that you rent a van and a hotel room. All of these costs add-up to $1000. You split the costs three-ways for a total of $333 each. At the last minute, your other friend (who we’ll call “Steve”) decides he can go on the trip. Steve thinks about it a bit and says, “Well, you guys are already paying for the car and hotel. There’s enough extra space for me and my stuff in the van. You’ve already got the hotel room, and I can sleep in there. This means I shouldn’t have to pay.” Nobody would be very happy about the idea of Steve getting a free trip. They say that Steve should have to pay, too — that each of you should pay $250. This is essentially what pirates are doing – acting like Steve. They say, “It doesn’t cost any extra money to add me. I should be allowed to get all the benefits but none of the costs.” This is essentially how creators view pirates – as people using self-interested logic to justify not having to bear any of the costs. Meanwhile, other people (the creator) has to bear the costs.

Sometimes people argue that businesses should price things at the “one additional user” cost. Since pirating something doesn’t impose additional costs on the creator, it should be okay to pirate stuff. The problem with this is that some businesses have large upfront costs that they need to spread out over lots of people. It’s actually not fair to the business to say that users don’t need to contribute to the overhead costs (i.e. that they should only have to pay their “one additional user” costs). Other industries which have a large upfront cost, but low per-user cost include:

* Concerts – The band and the stage show are a fixed cost. Whether there are 1,000 people in the audience or 5,000 doesn’t make a huge difference. If someone gets into the show for free, they don’t “use up” the sound going to other people’s ears. Yet, we don’t argue that people should be allowed into concerts for free (even if there’s space for additional people in the venue).

* Amusement parks – Amusement parks are rarely filled to capacity, but we don’t force them to allow people in for free. They charge a per-person cost (i.e. a ticket), but most of their costs are fixed, upfront costs (building the rides, electricity to power things). Their costs don’t really increase as more people enter the park.

* Movie theaters – There are a lot of times when movie theaters aren’t filled to capacity, but we don’t force them to allow people in for free. Most of their costs are fixed, upfront costs (building the movie theater, showing the movie). Whether there are 10 people or 100 people in the theater doesn’t affect the operating costs. Despite the fact that it doesn’t cost a movie theater anything to let one more person into the theater, we don’t force them to let us watch movies for free.

* Buses – The cost of a city bus or a long-distance bus is mostly a fixed cost (paying the driver, paying for gas). The weight of an additional passenger has a tiny effect on the buses’ costs. But, bus companies need to cover their full costs, which means charging passengers a rate that allows them to cover their overhead expenses.

* Hotels – When you pay $80 for a hotel room, that’s far in excess of the costs the hotel incurs because you’re staying there. But, building the hotel needs to be paid off (and that’s an investment in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars). The low cost of having someone in a hotel room is the reason that many Las Vegas hotels can offer free hotel rooms. If hotels were forced to charge people their “wholesale” cost, we’d all be paying something like $10 for hotel rooms. But, it would also mean that building hotels is extremely unprofitable because investors wouldn’t ever get their money back.

Fairness / An Exchange of Value

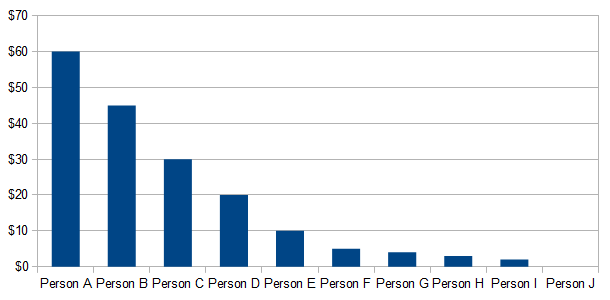

To look at it another way, if everyone rated on a scale of $0 to $100 how much they value a product, it might look something like this:

Now, according to economic theory, someone will buy a product if the price is lower than the value of a product. For example, if a product costs $35, but it has a value of $50 to you, then you will buy it and you’ll be effectively $15 wealthier. In this example, if we assume that our product costs $35, then two people in our example will buy it (Person A and Person B). The creator will earn $35×2 = $70 (which will, most likely, help pay off debt, so it’s not pure “profit”). The consumers value the product at $60+$40 = $100. They will be $30 wealthier (since they paid $70). The creator and the two consumers win.

Of course, one can ask “what about the other people?” Ideally, the creator will drop the price over time, and consumers will buy the product when it reaches a price-point that they want. (This generally happens with software and movies – games that are a few years old sell for cheap. See GoodOldGames for examples.) In a no-copyright environment, everyone gets a free copy. This leads to a very large benefit for society – in this case $60+$45+$30+$20+$10+$5+$4+$3+$2 = $179 of value. But, since the creator ends up with no money, he goes bankrupt and stops producing products. This is why I consider piracy to be the equivalent of “Killing the golden goose“. If the creator was smart, he probably wouldn’t have created the product in the first place, since there isn’t a decent way to get paid for his work. The result is that society ends up worse off in the long run.

This also puts the creator in the position of being a kind of sacrificial-lamb for society – producing $179 worth of value for society, but receiving no payment in return. It’s unfortunate that someone who creates so much value for society can’t get paid even a fraction of the monetary-value he has produced.

The benefits of the copyright system are that:

– Consumers get to decide whether or not they purchase a product after it has been completed. If you pay for a product before it is created, you never know if it will get completed or how it will turn out – and there are lots of ways products can go bad during development. For example, this Kickstarter board game (with $122,000 pledged) failed to produce anything. In other cases, games are created, but end up being bad (Masters Of Orion 3 comes to mind). Being a fan of the Masters Of Orion series, I might’ve funded the game before it was created, but, being created under “traditional” models means you get to see the product before you put any money down.

– It provides an incentive for creators to make great products that consumers want. While there are exceptions (good products that are financial failures; bad products that are financial successes), it’s true that a good product should sell better than a bad product. I appreciate the consumer-oriented approach this encourages. (An alternative system might be for society to pay creators a flat-rate via tax dollars. I don’t like this approach because it doesn’t reward good work and punish bad work.)

Counter-Arguments:

Counterarguments based around the Creation Costs

* Creators should use alternative funding models [No Link]

* Piracy takes money away from publishers/investors, not developers, because developers aren’t self-funded [No Link]

* People who pirate wouldn’t have bought it anyway, therefore, piracy never results in a loss of income [No Link]

Counterarguments based around Maximizing Value for Humanity

* Copyright shouldn’t last for decades; We should have short copyrights.

Return to “The Case Against Piracy”