I always like to know what other people think, even if I disagree with them, so I recently watched a video by Pirate Party founder Rick Falkvinge titled “Copyright Regime vs. Civil Liberties”. The Pirate Party is dedicated to copyright and patent “reform”, and by “reform”, they mean that they advocate elimination of almost all copyright, patent, and intellectual property laws. The only vestige of copyright that they support is to prevent commercial selling of copyrighted material for 5-10 years, and works would have to be attributed to their authors. Under the Pirate Party, filesharing would be legal, and all patents would be eliminated. They also support trademarks, because trademarks help society distinguish one creator from another.

Here’s the video, and (below) I’ve detailed what’s wrong with it:

Falkvinge’ main argument is this:

5:33-8:05

Copyright is at it’s heart a commercial monopoly. When it was created, it was created to distribute books to bookstores by horse and cart. And, the key thing there is that if you found an infraction of copyright, you can find a copied book in a bookstore, you can see an unauthorized concert (not paying license money). The key thing here is that you found them in public places – with the naked eye. Today, however, copyright has crept into my private communications. It is illegal for me to send a piece of music in email to you guys. It is illegal if we are in a chat channel, to drop a video clip there. And if copyright is to be enforced in this new environment, then that means all private communications must be monitored for copyright infractions. That means out goes the postal secret. That means law enforcement and corporate interest groups must monitor every 1 and 0 that leaves my computer. That includes looking at letters to my lawyer and doctor and wife. I’m frankly not prepared to give them that right… So, our poor lady justice has a problem: on one side of the scale, you have one income source for one entertainment industry – essentially a luxury consumption in our society. On the other side of the scale, you have two foundations of our democracy. Hmmmm.

Over the few minutes, Falkvinge goes into the consequences of monitoring all internet communications: whistleblowers no longer have protection, damage to freedom of the press, how this influences people to self-censorship, how your identity is formed by private communications with other people, etc.

11:00-11:30

So, the copyright industry would like you to believe that it is about somehow about right to profits. That the filesharing debate it is about percentages, about graphs on a piece of paper. It is not. It is about vital civil liberties that need to be eroded or abolished in order to maintain their old crumbling monopolies. And this is the message that we’ve started to get out in Sweden.

The whole situation sounds awful – like something out of 1984. Here’s the problem: Falkvinge’ argument is completely wrong. Everything Falkvinge says is correct if our goal is to stop every single instance of copyright infringement. However, the legal system has always recognized limits on law enforcement’s ability to pursue crimes. We can quickly see how flawed Falkvinge’ argument is if we simply insert a different crime in place of “copyright infringement” and repeat his argument. For example:

“And if [laws against child pornography] are to be enforced in this new environment, then that means all private communications must be monitored for [child pornography].”

“And if [laws against libel and slander] are to be enforced in this new environment, then that means all private communications must be monitored for [libel and slander].”

“And if [laws against false medical claims] are to be enforced in this new environment, then that means all private communications must be monitored for [false medical claims].”

If you believe that Falkvinge’ argument is valid for copyright, then you must advocate the elimination of lots of other laws. Further, if law enforcement’s goal is to eliminate all instances of any particular crime, without regard for people’s rights, then we might as well throw out all laws. Laws against burglary should be abolished because the only way to eliminate burglary is to put video cameras everywhere – and we can’t have that, therefore, we must abolish burglary laws. Laws against drugs should be abolished because the only way to eliminate the drug trade is to monitor everyone’s actions at every time, completely control all trade, and insert a device inside everyone’s body to monitor drug-levels at every moment. We can’t allow that, therefore, we must abolish drug laws.

So, the whole argument is just plain wrong. It’s true that copyright can be infringed through email-to-email communication, but, let’s face the facts here: that’s not how the vast majority of it happens, and second, even if 100% of copyright infringement happened through email, that’s not an argument that copyright laws should be abolished – it’s simply an argument that we will not be able to enforce copyright laws in particular cases. Falkvinge’ argument is that copyright cannot be enforced on private communications, therefore the laws should be abolished. Abolishing copyright means we can no longer prosecute public violations of copyright. In short: he’s arguing that we shouldn’t be able to prosecute public violations of copyright because sometimes copyright is privately violated.

Alternatively, we could simply enforce copyright whenever someone sticks out their neck and violates copyright in public. In fact, this is where the vast majority of copyright infringement happens anyway. Combating piracy is a very open-ended problem; there are numerous possible ways to combat it. It is disingenuous of Falkvinge to pretend that the one and only way to combat copyright violations is through monitoring all internet communication.

I’ve actually seen this quite a few times from the anti-copyright crowd: this attempt to connection copyright elimination with “saving human culture” or “protecting our fundamental freedoms”. It gives them the opportunity to twist-around “not paying the creator for their work” into a saintly “I’m fighting for our freedom against greedy corporations”.

Besides, if Falkvinge’ argument was true, then there’s a major problem for him. The stance of the Pirate Party is that copyrights should last for 5-10 years, and they only restrict what you can buy and sell. This means, for example, that Walmart cannot print-up their own copies of books and sell them during that 5-10 year window. But, I can go online right now and purchase a pirated copy of software. I’ve seen the websites. So, the question is this: if I buy copyrighted material from some illegal vendor over the internet (maybe through email, maybe through a website), then that is “private communication”. By Falkvinge own argument, we HAVE to allow this type of activity because the only way to stop it is by monitoring all internet communication. Therefore, the 5-10 year restriction on selling copyrighted material is unenforceable, and should be abolished. The Pirate Party’s stance is internally inconsistent.

Now, the Pirate Party might argue that a website selling pirated material on the internet is “public”, but how is that any more public than filesharing websites?

So, the major argument of Falkvinge’ “Copyright Regime vs Civil Liberties” talk is 100% wrong.

7:00-7:40

And it gets worse. The copyright is now lobbying for ISPs to be liable for what their users do on the net. And there goes another very important principle called the “common carrier principle” which ways that the messenger is never responsible for the contents of the message. Imagine if the US postal service would be held liable for what you send in letters. This is what the copyright industry is lobbying for. And they’re taking advantage of the fact that politicians are clueless about what new technology means.

There is a grain of truth in Falkvinge’ argument here, but it’s not nearly as bad as he wants us to believe. He wants us to believe that the ISP can be held guilty for the crime committed over the internet connection. For example, it sounds like an ISP can be held responsible for a death-threat send via email by one of their users. This is not actually what “holding the ISP responsible” means. Falkvinge’ statement is actually vague on this issue – which makes people assume the worst. (You can read more about this issue here.)

It’s currently two years after he gave his talk, and it’s true that copyright groups have started working with ISPs to cut-off internet service to pirates. I have actually heard about people receiving warning letters from their ISPs about pirating material over the internet. In one case, an internet user received a letter about a specific movie they had pirated on a specific day. They didn’t cut off his service, but it’s possible that they would after the third infraction. There are already some parallels with the policy of cutting-off pirates. For example, ISPs are sometimes contacted about cutting off customers who send spam, or who are involved in port scanning (which is typically associated with computer hacking). I’m sure that, if there is a grain of truth in Falkvinge’ argument, it might be true that the copyright industry is lobbying to get the right to sue ISPs who ignore piracy by specific users even after the ISP has been repeatedly notified about those users. In that sense, the ISP would be liable for failing to act on specific complaints about infractions by specific users. Falkvinge could then twist that into ISPs are going “to be liable for what their users do on the net”, which is true or false depending on how you interpret it.

I completely agree that ISPs should not have to monitor their users, or be held responsible for first-time infractions of their users. However, if an ISP repeatedly ignores notifications about a particular user, then it’s reasonable that their liability should increase. There is similar to how copyrighted material is treated on the web. If the copyright holder finds their material on the internet, they can send a cease-and-desist letter. You can then remove the offending material with no consequences. However, if you ignore the letter, your liability increases. This is why YouTube doesn’t get sued into bankruptcy – they don’t have to police every video uploaded onto YouTube for copyright violations, but they can be held liable if they ignore cease-and-desist letters about specific videos. In effect, ignoring cease-and-desist letters is tantamount to providing safe-harbor for copyright violators. I suppose someone could (just as truthfully) make the statement that “YouTube is being held liable for the actions of its users” – which is also true or false, depending on how you interpret it. (This is what gets a lot of piracy websites into trouble: they ignore cease and desist letters.)

11:40-18:00

Falkvinge gives his history of copyright and why it exists. His basic narrative is that the Catholic Church “was one source of culture and knowledge”. It was a top-down, one-source to “the masses” type of communication. Then, the printing press came along. The English monarchy established a single group of printers who could print books for authors, but censor and burn books not wanted by the crown. Later, when England allowed more freedom of the press, they also allowed more people to print books. The printers then pushed to establish “copyright” so that they could control printing of works by authors. He claims that it was always about protecting the distributor’s profits, never about protecting the author. I think the main point he is trying to make here is to establish a pattern: the Catholic Church controlled everything (bad), but then the printing presses came along (more distributors=good). But, the monarchy locked down the printing presses with censorship and ‘authorized printers’ (bad). Eventually, freedom of the press was established and more printers were allowed (good), but the ‘old system’ didn’t like that. He seems to be trying to create the pattern in the listener’s mind of the ‘old system’ trying to control things, but the ‘new way’ was always better and more democratic. While his point was muddled, he seems to trying to argue that ‘filesharing’ is the new democratic distributor which is opposed to the ‘old system’ of copyright.

This isn’t so much an actual argument as it is an attempt to get the listener’s mind thinking along a particular pattern and then insert filesharing into the sequence to guide the listener to a predefined conclusion. This type of argument is just “patterning”, and while it might confuse people into believing your pet theory, it has some big logical flaws. It’s easy to setup a pattern and then fit your own pet theory into it. For example, you could argue that the “old system” has always resisted the “new system”, but the new system was always better. Monarchy resisted democracy, but democracy was better. The Ptolemaic astronomers resisted Galileo, but Galileo was right. Governments resisted free speech, but free speech was better. Then, once you’ve established a pattern to get the listener to think in a particular direction, throw in your pet theory that superficially fits the pattern: and capitalism (the old system) will resist communism (the new system), but communism is better. Of course, that’s nonsense. I mostly see “patterning” arguments used with pseudoscience. Some crackpot will say that the establishment resisted Galileo and laughed at Einstein, and then imply that he fits the same pattern. Of course, he conveniently ignores the fact that 99 out of 100 theories turn out to be completely wrong. In the end, “patterning” is just rhetoric – a way to convince people you’re right without actually putting forward reasoned arguments.

17:18-18:00

So, the key here is that copyright, while written into law that it’s supposed to be for the benefit of the author, never was. It was for the benefit of the distributors. It was lobbied by the old monopoly as a way for that monopoly to remain even after the authors has supposedly gotten it instead…

Falkvinge is trying to setup the idea that authors/creators (the people we like) don’t benefit from copyright but (faceless, greedy) distributors make loads of cash from copyright. I’m sure most authors and creators see this as nonsense, but Falkvinge can probably pull the wool over the public’s eyes on this one. Heck, it’s almost an argument that you should pirate because (according to him) buying only helps greedy distributors and never the author.

19:43-20:15

What we’re saying is that, okay, there might be some business models that require a time-limited monopoly. Like, I can imagine a $200 zillion dollar movie out of Hollywood might want some sort of time-limited monopoly in order to get all of that venture capital. But, that monopoly must really now stretch into my private communication. I’m sorry, but the buck stops there… Non-commercial usage must be let free.

This is his argument about why filesharing should be legal, but they’re going to allow a 5-year monopoly on commercial trade. (Nevermind the fact that filesharing will drop the bottom out of any commercial trade.)

20:55-21:40

We have as vision a society where every citizen has 24/7 access to all of humanity’s collected knowledge and culture anywhere. That is a huge leap-forward. It is not a bad thing that the copyright industry has to take a step back. This is a much larger leap ahead than when public libraries arrives 150 years ago. And it is now enabled by today’s technology.

Actually, society already has that access. What Falkvinge wants is free access, and free access at the expense of the creator who produced it. Our copyright system enables the continued creation of new work. Economists know there is no such thing as a free lunch, but Falkvinge hasn’t figured that out yet. And the comparison to libraries is faulty. Libraries support authors by buying books. He might have a point if libraries printed up their own copies of books (without paying the author), and also printed up free, permanent copies for anyone.

I also hate the “knowledge and culture” phrase that anti-copyright advocates use because they want to make “entertainment” sound lofty and legitimize making it free. Anyway, more and more information is freely available on the web. Dictionaries and encyclopedias, for example. More and more TV and movies are available online – with only a few advertisements. There is so much information available on the internet for free, more than anyone could ever read. We have more free “knowledge and culture” available at our fingertips than anyone at any other period of history. All of this actually makes it clear that the Pirate Party isn’t really interested in spreading knowledge. They want free access to all the movies, music, and software that they can get. It’s about free entertainment, about never having to pay for anything digital. (A quick look at the top downloads at piracy websites will quickly reveal that entertainment is the primary goal of pirates.)

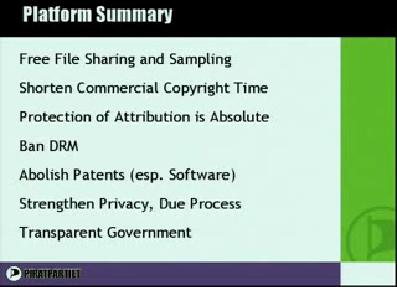

He sums up the Pirate Party positions:

The only items where I really agree with his ideas are shortening copyright lengths (but not as extreme as lowering it to 5-years) and also reducing patents (to cut out all the frivolous, defensive patents, but not to eliminate all patents).

29:00-29:15

What’s important about this is that every single business model that makes money today will make money with these changes implemented. The only difference is that millions of people will not be criminals.

It’s hard to interpret exactly what he means by this statement. It could have two possible meanings:

(1) He’s claiming that the business models will bring in the same levels of revenue as they did under a copyright system, and therefore, creators will continue to create.

(2) He’s claiming that those business models will “make money” without copyright, but avoids saying that they make a lot less money. This obviously true – no businesses will bring in zero dollars in revenue, but it’s irrelevant since a company that makes 20% of its original revenue is probably a bankrupt company.

So, I’ll address the first interpretation, which is the only relevant question here. Because companies and creators have a variety of costs and variable profitability, Falkvinge essentially has to argue that people will continue to pay as much money to creators if copyright is eliminated. Presumably, he thinks that people will simply donate money – and they’ll donate just as much money to support creators as they currently spend to buy copyrighted material, or purchase copies (even though they already have the media). This sounds like complete nonsense. I’m sure that if you compared the amount of money donated to OpenOffice versus the amount of money paid to Microsoft for MS Office, you’d find a huge disparity. (And I say that not because I’m crying for big-companies or their potential loss, but simply to point-out that people do not donate nearly enough to match what they were paying for copyrighted material.) Similarly, wikipedia has never earned nearly as much money in donations as Encyclopedia companies were earning back in the 1980s. More specifically, wikipedia was trying to raise $6 million in donations in 2008. In comparison, the Encyclopedia Britannica brought-in $800 million in 1989. It’s great that there’s a free encyclopedia for everyone, but my point is simply that people are clearly not donating at levels that replace revenue compared to copyright systems.

Now, I know that people argue that pirates purchase a lot of digital after they pirate it. (I don’t actually believe that most pirates continue to buy at levels near their pre-piracy rates.) I also doubt that a good comparison can be made between the behavior of pirates and the behavior of the general public in a society without copyright over a long period of time. Sometimes, I think pirates purchase copies of material they pirate because they’re still in the habit of buying digital media from their pre-piracy days (thanks to copyright). I think that companies will see revenues fall to a small fraction of their current earnings if copyright is eliminated. That may not be a problem for the survival of a few extremely profitable products, but it will bankrupt almost everyone else.

I think the Pirate Party’s ideas are bad economics, and has quite a bit in common with other bad economic systems that got people excited, but were fundamentally flawed (like communism and the dot-com bubble). Unfortunately, “free entertainment” is a pretty good way to draw-in votes, especially among younger people – who are cash-strapped and very interested in entertainment.

Update: From an 19 October 2009 BBC article –

[Falkvinge] takes a long pause when asked whether he agrees with the principle that artists should be allowed to make a living from their creations, if they are popular enough.

“In economic terms, there is an enormous oversupply of people wanting to live off creativity,” he replies.

“So there isn’t enough demand to pay everybody. In such an occasion, market forces dictate that there will only be so many successful creators.”

First of all, he actually dodged the question. It reminds me of that adage politicians follow: don’t answer the question that was asked, answer the question that you wish they asked.

Second, the reality is that all economic systems require laws to function well. If you own a store, you need laws against shoplifting, embezzlement, and laws involved in contracts (so that, for example, you can require that your suppliers hold-up their end of the bargain). If the government suddenly decided that shoplifting was okay, you’d see stores taking drastic action to stop theft (e.g. guns) and lots of stores going bankrupt. The fact that they go bankrupt is not a symptom of “market forces dictating that there will only be so many successful [stores]”. That would misattribute the reason for the failure, and would be an attempt to dodge the blame for setting up a bad economic system.

The Pirate Party wants to change the economic system and make it much harder for creators to recoup the value that they have produced for society. Then, under this biased economic system, when creators fail, they point to “the market” as the reason that the creator failed. In reality, when a customer buys a product for $10, what they are saying is that “this product is worth more to me than the $10 I have in my pocket”. The Pirate Party, by eliminating copyright, would be opening the doors for everyone to get it all for free – which would eliminate ability to make a mutually-beneficial trade, just as legalizing shoplifting would eliminate the ability to make mutually-beneficial trade between the store and the customer. Customers get this valuable product for free, the creator goes bankrupt and stops producing for society. It’s not because “the market” decided that the creator wasn’t producing value for society, but rather, because the economic system was changed so that the value that the creator produced would no longer be repaid by society to the creator. So, what Falkvinge is doing here is revealing how badly he would bungle the economic system that encourages production, and how poorly he understands the economic and legal underpinnings of society.

In economic terms, eliminating copyright is a loss for society. It’s a “tragedy of the commons” situation. When everyone pursues their own self-interest (by pirating and not paying) it leads to a collapse of the economic system that enables creators to continue their work:

The tragedy of the commons refers to a dilemma described in an influential article first published in the journal Science in 1968. The article describes a situation in which multiple individuals, acting independently, and solely and rationally consulting their own self-interest, will ultimately destroy a shared limited resource even when it is clear that it is not in anyone’s long-term interest for this to happen.

Pingback: Thoughts of a Game Developer » Slashdot and Piracy

I’m against intellectual property laws myself. I think you’re right about his arguments (I wasn’t reading too closely). But to be fair rhetoric is a part of all political advocacy. Much more reasoned arguments have been made. David Levine and Michele Boldrin make a good case against intellectual property laws in their book Against Intellectual Monopoly. It’s cited on the Wikipedia article on intellectual property, so you can get there (in PDF format). I found it pretty convincing even though I’m not that far in it. But judge for yourself.

I see from another article that you find it difficult to even read what the anti-copyright advocates have got to say. That depresses me a little. I hope you read my comments. You might enjoy the book I suggested, because it certainly has rational, well-founded arguments, even if it’s wrong. I really do hope you read it, because I don’t want to be seen as an irrational person T_T.

(nod) I recently found Lessig’s book, Free Culture, online as well. I have to admit, though, that I’m not very convinced by his arguments. Many of his points in the book seem to be the same ones he raised in his TED talk.

Your point about his slippery slope from copyright to communication intercepting is astute, it appears he has some grounds to stand on. He does say that in the EU, if a crime’s punishment is determined to be 4 years (I believe) then that crime is a candidate for the use of warrantless wiretapping. This does not seem to be the case in the U.S. and I haven’t done the research to back up his claim, but it seems he’s not just making a slippery slope fallacy here, but speaking to a real and present danger that is being pushed by European lawyers on behalf of media companies.